The Wildlands Network

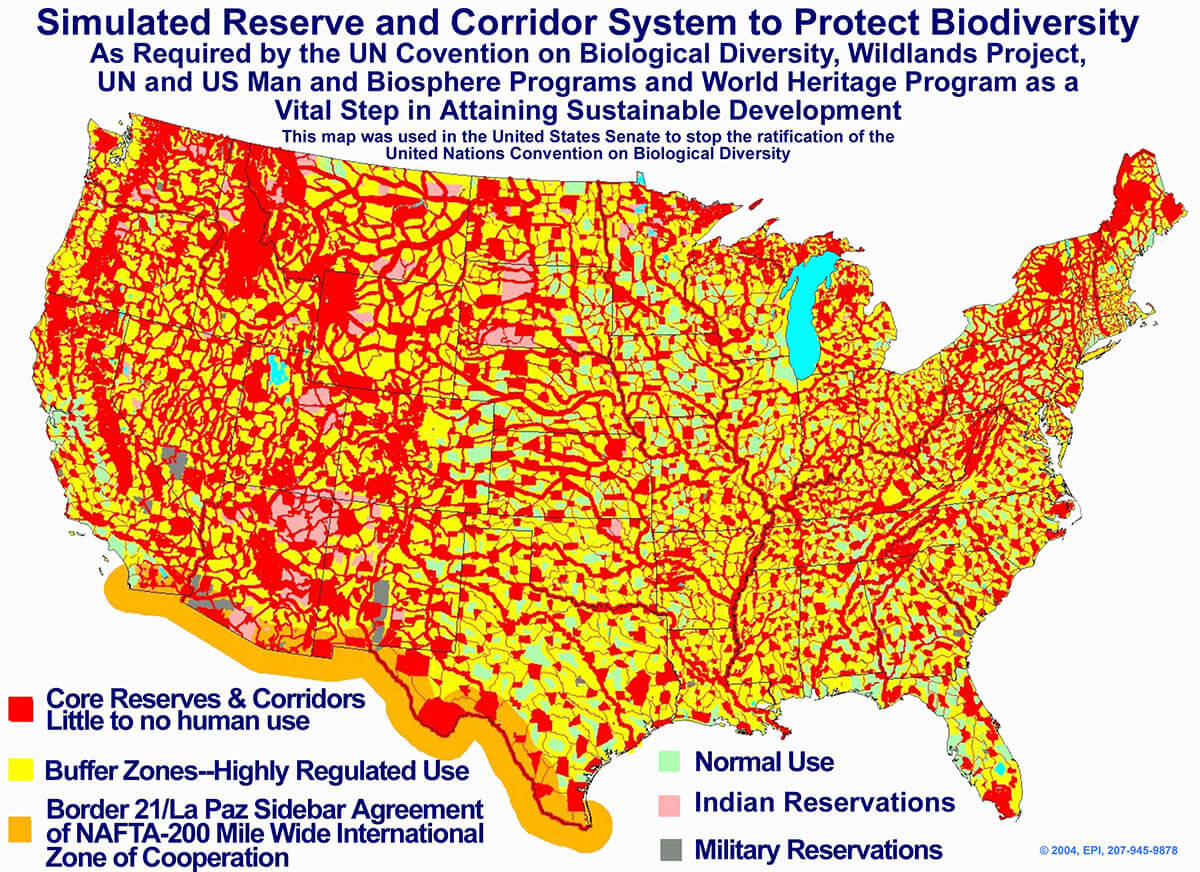

THE WILDLANDS NETWORK (formerly called The Wildlands Project) (NOTE: This map, which was originally on The Wildlands Project website, has been removed from their new website: www.wildlandsnetwork.org/. A picture is worth a thousand words. Perhaps it was too upsetting for people.)

Below is an article written by Henry Lamb and published on www.Sovereignty.net. Rosa Koire of Democrats Against UN Agenda 21 finds this “to be the best, most concise description of the actual and potential impacts of UN Agenda 21 that we have found.” Mr. Lamb is a truth teller and freedom fighter and this article is well worth your time to read.

Special Report Sustainable Development: Transforming America by Henry Lamb (published on December 1, 2005)

As the “sustainable development” movement continues to gain momentum, it is worthwhile to step back and take a long look at the big picture, painted with a broad brush to reveal what the United States might look like as the movement’s vision is more fully implemented over the next 50 years or so.

The picture painted here is based on official documents published by several government agencies and non-government organizations during the last decade. These documents were rarely reported in the news, and average working people have no idea what sustainable development really means, and even less knowledge of what is in store for the future. If the vision of sustainable development continues to unfold as it has in the last decade, life in the United States will be quite different in the future.

The Vision

Half the land area of the entire country will be designated “wilderness areas,” where only wildlife managers and researchers will be allowed. These areas will be interconnected by “corridors of wilderness” to allow migration of wildlife, without interference by human activity. Wolves will be as plentiful in Virginia and Pennsylvania as they are now in Idaho and Montana. Panthers and alligators will roam freely from the Everglades to the Okefenokee and beyond.

Surrounding these wilderness areas and corridors, designated “buffer zones” will be managed for “conservation objectives.” The primary objective is “restoration and rehabilitation.” Rehabilitation involves the repair of damaged ecosystems, while restoration usually involves the reconstruction of natural or semi-natural ecosystems. As areas are restored and rehabilitated, they are added to the wilderness designation, and the buffer zone is extended outward.

Buffer zones are surrounded by what is called “zones of cooperation.” This is where people live – in “sustainable communities.” Sustainable communities are defined by strict “urban growth boundaries.” Land outside the growth boundaries will be managed by government agencies, which grant permits for activities deemed to be essential and sustainable. Open space, to provide a “viewshed” and sustainable recreation for community residents will abut the urban boundaries. Beyond the viewshed, sustainable agricultural activities will be permitted, to support the food requirements of nearby communities.

Sustainable communities of the future will bear little resemblance to the towns and cities of the 20th century. Single-family homes will be rare. Housing will be provided by public/private partnerships, funded by government, and managed by non-government “Home Owners Associations.” Housing units will be designed to provide most of the infrastructure and amenities required by the residents. Shops and office space will be an integral part of each unit, and housing will be allocated on a priority basis to people who work in the unit – with quotas to achieve ethnic and economic balance. Schools, daycare, and recreation facilities will be provided. Each unit will be designed for bicycle and foot traffic, to reduce, if not eliminate, the need for people to use automobiles.

Transportation between sustainable communities, for people and for commodities, will be primarily by light rail systems, designed to bridge wilderness corridors where necessary. The highways that remain will be super transport corridors, such as the “Trans-Texas Corridor” now being designed, which will eventually reach from Mexico to Canada. These transport corridors will also be designed to bridge wilderness corridors, and to minimize the impact on the environment.

Government, too, will be different in a sustainable America. Human activity is being reorganized around eco-regions, which do not respect county or state boundaries. Therefore, the governing apparatus will be designed to regulate the activities within the entire region, rather than having multiple governing jurisdictions with services duplicated in each political subdivision. It is far more efficient to have regional governing authorities with centrally administered services.

The Sierra Club, one of hundreds of non-government organizations actively working to bring about this transformation, has suggested that North America be divided into 21 eco-regions, that ignore existing national, state, and county boundaries. In 1992, they published a special issue of their magazine which featured a map, and extensive descriptions of how these eco-regions should be managed.(1)

The function of government will also change. The legislative function, especially at the local and state level, will continue to diminish in importance, while the administrative function will grow. Already, in some parts of the country, counties are combining, and city and county governments are consolidating. Regional governing authorities are developing; taking precedence over the participating counties, which will eventually evaporate. State governments will undergo similar attrition; as regulations are developed on an eco-regions basis, there will be less need for separate state legislation. The administrative functions of state governments will also collapse into a super-regional administrative unit, to eliminate unnecessary duplication of investment and services.

The Reality

This vision is quite attractive to many Americans, especially those born since 1970, who have been educated in the public school system. To these people, nothing is more important than saving the planet from the certain catastrophe that lies ahead, if people are allowed to continue their greedy abuse of natural resources. The public school system, and the media, have been quite successful is shaping new attitudes and values to support this vision of how the world should be.

This vision did not suddenly spring from the mind of a Hollywood screenwriter. It has been evolving for most of the last century. Since the early 1960s, it has been gaining momentum. The rise of the environmental movement became the magnet which attracted several disparate elements of social change, now coalesced into a massive global movement, euphemistically described as sustainable development.

The first Wilderness Act was adopted in 1964, which set aside nine million acres of wilderness so “our posterity could see what our forefathers had to conquer,” as one Senator put it. Now, after 40 years, 106.5 million acres are officially designated as wilderness.(2) At least eight bills have been introduced in the 109th Congress to add more wilderness to the system.(3) And every year, Congress is asked to designate more and more land as wilderness. Most of this land is already a part of a global system of eco-regions, recognized internationally as “Biosphere Reserves.”

In the United States, there are 47 Biosphere Reserves, so designated by the United Nations Education, Science, and Cultural Organization,(4) which are a part of a global network of 482 Biosphere Reserves. This global network is the basis for implementing the U.N.’s Convention on Biological Diversity,(5) a treaty which the U.S. Senate chose not to ratify.(6) The 1140-page instruction book for implementing this treaty, Global Biodiversity Assessment, provides graphic details about how society should be organized, and how land and resources should be managed, in order to make the world sustainable. This treaty was formulated by U.N. agencies and non-government organizations between 1981 and 1992, when it was formally adopted by the U.N. Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro.

Consider this instruction from the Global Biodiversity Assessment:

“…representative areas of all major ecosystems in a region need to be reserved, that blocks should be as large as possible, that buffer zones should be established around core areas, and that corridors should connect these areas. This basic design is central to the recently proposed Wildlands Project in the United States.”(7)

Now consider “this basic design” as described in the Wildlands Project:

“…that at least half of the land area of the 48 conterminous states should be encompassed in core reserves and inner corridor zones (essentially extensions of core reserves) within the next few decades…. Nonetheless, half of a region in wilderness is a reasonable guess of what it will take to restore viable populations of large carnivores and natural disturbance regimes, assuming that most of the other 50 percent is managed intelligently as buffer zones. Eventually, a wilderness network would dominate a region…with human habitations being the islands. The native ecosystem and the collective needs of non-human species must take precedence over the needs and desires of humans.” (8)

Even though this treaty was not ratified by the United States, it is being effectively implemented by the agencies of government through the “Ecosystem Management Policy.” The U.S. Forest service is actively working to identify and secure wilderness corridors to connect existing core wilderness areas.(9)

Both state and federal governments have enacted legislation in recent years to provide for systematic acquisition of “open space,” land suitable for restoration and rehabilitation, to expand wilderness areas, and to provide “viewsheds” beyond urban boundaries.

In the last days of the Clinton Administration, the Forest Service adopted the “Roadless Area Conservation Rule,” which identified 58.5 million acres from which access and logging roads were to be removed. In the West, the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management are driving ranchers off the land by reducing grazing allotments to numbers that make profitable operations impossible. Inholders, people who have recreational cabins on federal land, are discovering that their permits are not being renewed. The Fish and Wildlife Service is forcing people off their land through designations of “wetlands,” and “critical habitat” which render the land unusable for profit-making activities.

Much to the chagrin of the proponents of sustainable development, some of these policies have been slowed, but not reversed, by the Bush administration. Nevertheless, agencies of government, supported by an army of non-government organizations, continue to transform the landscape into the vision described in the Wildlands Project, and in the Global Biodiversity Assessment.

Other agencies of government are working with equal diligence, to create the “islands of human habitation,” otherwise called sustainable communities. The blueprint for these communities was also adopted at the 1992 U.N. Conference in Rio de Janeiro. Its title is “Agenda 21.” This 300-page document contains 40 chapters loaded with recommendations to govern virtually every facet of human existence. Agenda 21 is not a treaty. It is a “soft law” policy document which was signed by President George H.W. Bush, and which does not require Senate ratification.

One of the recommendations contained in the document is that each nation establish a national council to implement the rest of the recommendations. On June 29, 1993, President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order Number 12852 which created the President’s Council on Sustainable Development.(10) Its 25 members included most Cabinet Secretaries, representatives from The Nature Conservancy, the Sierra Club and other non-government organizations, and a few representatives from industry.

The PCSD set out to implement the recommendations of Agenda 21 administratively, where possible, and to secure new legislation when necessary. One of the publications of the Council is “Sustainable Communities, Report of the Sustainable Communities Task Force.”(11) This document, in very generalized language, makes sustainable communities sound like the perfect solution to all the world’s ills. Another document, however, describes in much more precise detail exactly what sustainable communities will be. This document was prepared by the Department of Housing and Urban Development as a report to the U.N. Conference on Human Settlements in Istanbul, June, 1996.

This report says that current lifestyles in the United States will “…demolish much of nature’s diversity and stability, unless a re-balance can be attained – an urban-rural industrial re-balance with ecology, as a fundamental paradigm of authentic, meaningful national/global human security.”(12)

This highly detailed 25-page report goes on to describe the sustainable community of the future:

“…Community Sustainability Infrastructures [designed for] efficiency and livability that encourages: in-fill over sprawl: compactness, higher density low-rise residential: transit-oriented (TODs) and pedestrian-oriented development (PODs): bicycle circulation networks; work-to-home proximity; mixed-use-development: co-housing, housing over shops, downtown residential; inter-modal transportation malls and facilities …where trolleys, rapid transit, trains and biking, walking and hiking are encouraged by infrastructures.”

“For this hopeful future we may envision an entirely fresh set of infrastructures that use fully automated, very light, elevated rail systems for daytime metro region travel and nighttime goods movement, such as have been conceptualized and being positioned for production at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis; we will see all settlements linked up by extensive bike, recreation and agro-forestry “E-ways” (environment-ways) such as in Madison, Wisconsin; we will find healthy, productive soils where there is [now] decline and erosion, through the widespread use of remineralization from igneous and volcanic rock sources (much of it the surplus quarry fines, or “rockdust”, from concrete and asphalt-type road construction or from reservoir silts); we will be growing foods, dietary supplements and herbs that make over our unsustainable reliance upon foods and medicines that have adverse soil, environmental, or health side-effects. Less and less land will go for animal husbandry, and more for grains, tubers and legumes.” (13)

Sustainable communities cannot emerge as the natural outgrowth of free people making individual choices in a free market economy. Nor can they be mandated in the United States, as they might be in nations that live under dictatorial rule. Therefore, the PCSD developed a strategy to entice or coerce local communities to begin the transition to sustainability.

The EPA provided challenge grants, and visioning grants to communities that would undertake the process toward sustainability. Grants were also made available to selected non-government organizations to launch a visioning process in local communities. This process relies on a trained facilitator who uses a practiced, “consensus building” model to lead selected community participants in the development of “community vision.” This vision inevitably sets forth a set of goals – each of which can be found in the recommendations of Agenda 21 – that become the basis for the development of a comprehensive community plan.(14)

According to the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), 6,400 local communities in 113 countries have become involved in the sustainable communities Local Agenda 21 process since 1995. (15) ICLEI is one of several international non-government organizations whose mission is to promote sustainable development and sustainable communities at the local level. Dozens of similar national NGOs are at work all across the United States. A cursory search on the term “sustainable communities” through Google or Yahoo will return a staggering number of responses.

The federal government deepened its involvement in the transformation of America by providing millions of dollars in grants to the American Planning Association to develop model legislation which embodies the principles of sustainable development. The publication, Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook: Model Statutes for Planning and the Management of Change, provides model legislation to be adopted by states. Typically, this legislation, when adopted, requires the creation of a statewide comprehensive land use plan that defines the administrative mechanisms for regional government agencies, and provides planning models for counties to use in creating county-wide land use plans. Municipalities within the county are required to produce a plan that conforms with, and is integrated into the county and state plans.(16)

Using the coercive power of the federal budget, which the PCSD describes as using “financial incentives and disincentives,” the federal government had little trouble getting states to rush to adopt some form of the model legislation. The state of Wisconsin, for examples, says this about its comprehensive planning act:

“The Comprehensive Planning Law was developed in response to the widely held view that state planning laws were outdated and inconsistent with the current needs of Wisconsin communities. Commonly recognized as Wisconsin’s “Smart Growth” legislation, significant changes to planning-related statutes were approved through the 1999-2001 state biennial budget. Under the new law, any program or action of a town, village, city, county, or regional planning commission, after January 1, 2010, that affects land use must be guided by, and consistent with, an adopted Comprehensive Plan, s. 66. 1001, Wis. Stats.”(17)

The APA’s Legislative Guidebook offers several forms of the model legislation. States have considerable latitude in the legislation that is adopted. Consequently, each state’s legislation may be different, and may impose different requirements on county and city governments. Regardless of the difference, however, they all contain the basic principles set forth in Agenda 21, and they all require the development of plans that result in the implementation of the recommendations contained in Agenda 21.

One of the fundamental elements of all the plans requires limiting development (growth) to certain areas within the county. Planners draw lines on maps, supposedly to prevent development in “environmentally sensitive” areas, but which, in fact, are often quite arbitrary and sometimes influenced by political considerations. The value of land inside the development areas skyrockets, while the value of land outside the development areas plummets – with no hope of future appreciation.

Another common element of these plans is to limit the activity that may occur within the various plan designations. In King County, Washington, for example, property owners in some parts of the county are required to leave 65% of their land unused, in its “natural” condition.

“Known as the 65-10 Rule, it calls for landowners to set aside 65 percent of their property and keep it in its natural, vegetative state. According to the rule, nothing can be built on this land, and if a tree is cut down, for example, it must be replanted. Building anything is out of the question.”(18)

These plans also focus on reducing automobile use. Measures sometimes include making driving less convenient by constructing speed bumps and obstructive center diversions on residential streets, prohibiting single occupant use of certain traffic lanes, as well as a variety of extra “tax” measures for auto use. Oregon is experimenting with a mileage tax, based on miles driven. London has imposed a special tax on automobiles that enter a designated “high traffic area.” Several U.S. cities are studying this idea. Santa Cruz, California’s plan seeks to ban auto use in certain municipal areas. Hundreds of NGOs have popped up to form a “World Carfree Network” (19) which lobbies local officials to reduce or eliminate auto use.

Alternative transportation is another common element of these plans. Light rail is a favorite, even in communities that have no hope of achieving economic viability. Proponents of sustainable development argue that even if a light rail system has to be subsidized forever, it is a bargain just to get automobiles off the streets. Bicycle paths and “Trails” are always a substantial part of sustainable community plans.

Housing in sustainable communities presents special problems. Space limitations, imposed by growth boundaries, force higher densities and smaller housing units. The term “McMansions” has been coined to describe new homes that are larger than necessary, as determined by sustainable development enthusiasts. Multiple housing units are preferred over single-family structures. Since sustainable communities cannot grow horizontally, they must grow vertically – if they grow at all.

These problems have produced a variety of responses. Some of the new terms that are becoming common in sustainable communities are: Limited Equity Co-ops; Resident-controlled Rentals; Co-housing; Mutual Housing; and many others.(20) Invariably, these schemes are alternatives to the conventional single-family home. Most often, these schemes vest ownership in a corporation that owns the housing units, and residents may, but not always, own shares of the corporation. Living conditions are determined, not by the individual resident, but by the corporation. Financing for the construction of these units, typically requires construction to meet “sustainable” standards, if federal money is used, either directly or indirectly, as in a mortgage guarantee.

Single family homes and business structures that already exist when a community is transformed to sustainability are a special problem, since they rarely meet the criteria required by the comprehensive plan. APA’s Legislative Guidebook offers a new solution for this problem: “Amortization of Non-Conforming Uses.” This means that a city or county may designate a period of time in which existing structures must be brought into conformity with the new regulations.

“But for homeowners who live in a community that adopts the Guidebook’s vision, the APA amortization proposal means the extinguishing, over time, of their right to occupy their houses, and without just compensation for loss of that property. How long they have before they must forfeit their homes would be completely up to the local government.”(21)

Eminent domain is another tool used by government to bring their communities into compliance with the sustainable communities vision. With increasing frequency, governments have used this technique to take land, not for “public use,” as required by the U.S. Constitution, but for whatever the government deems to be a “public benefit.”(22) Governments may condemn and seize the private property of an individual, and then give, or sell it, to another private owner who promises to use the property in a way that satisfies the government’s vision.

Plans adopted at the local level can have extremely detailed requirements. It is not unusual for these plans to specify the types of vegetation that must be used for landscaping, the color of paint to be used – inside and outside the structure, and even the types of appliances and fixtures that must be used. Businesses can be required to use signs that conform in size and color to all the other signs in the neighborhood. There is virtually no limit to the restrictions that these plans may impose.

These comprehensive plans are often complicated by an assortment of sub-authorities, such as Historic Districts; Conservation Districts; Economic Development Districts; Scenic Highways and Byways; Scenic Rivers and Streams; and more. These quasi-government agencies are most often created by ordinance, and populated with political appointees. They are frequently given unwarranted authority to dictate the use of private property within their jurisdiction. Individuals caught up in conflict with these agencies are often frustrated by the indifference of elected officials, and financially drained by the legal costs required to resist their dictates.

In one form or another, sustainable development has reached every corner of the United States. It has impacted millions of Americans, most of whom have no idea that their particular problem is related to a global initiative launched more than 15 years ago, by the United Nations. Many, if not most of the bureaucrats at the local and state level, charged with implementing these policies, have no knowledge of their origin. What’s worse, few people have considered the possible negative consequences of these policies.

Consequences of Sustainable Development

What is perhaps the most serious consequence of sustainable development is the least visible: the transformation of the policy-making process. The idea that government is empowered by the consent of the governed is the idea that set the United States apart from all previous forms of government. It is the principle that unleashed individual creativity and free markets, which launched the spectacular rise of the world’s most successful nation. The idea, and the process by which citizens can reject laws they don’t want, simply by replacing the officials who enacted them, makes the ballot box the source of power for every citizen, and the point of accountability for every politician.

When public policy is made by elected officials who are accountable to the people who are governed, then government is truly empowered by the consent of the governed. Sustainable development has designed a process through which public policy is designed by professionals and bureaucrats, and implemented administratively, with only symbolic, if any, participation by elected officials. The professionals and bureaucrats who actually make the policies are not accountable to the people who are governed by them.

This is the “new collaborative decisions process,” called for by the PCSD.(23) Because the policies are developed at the top, by professionals and bureaucrats, and sent down the administrative chain of command to state and local governments, elected officials have little option but to accept them. Acceptance is further ensured when these policies are accompanied by “economic incentives and disincentives,” along with lobbying and public relations campaigns coordinated by government-funded non-government organizations.

Higher housing costs are an immediate, visible consequence of sustainable development. Land within the urban growth boundary jumps in value because supply is limited, and continues to increase disproportionately in value as growth continues to extinguish supply. These costs must be reflected in the price of housing. Add to this price pressure, the regulatory requirements to use “green seal” materials; that is, materials that are certified, either by government or a designated non-government organization, to have been produced by methods deemed to be “sustainable.”

Higher taxes are another immediate, visible, and inevitable consequence of sustainable development. Higher land values automatically result in higher tax bills. Sustainable development plans include another element that affects property taxes. Invariably, these plans call for the acquisition of land for open space, for parks, for greenways, for bike-and- hike trails, for historic preservation, and many other purposes. Every piece of property taken out of the private sector by government acquisition, forces the tax burden to be distributed over fewer taxpayers. The inevitable result is a higher rate for each remaining taxpayer.

Another consequence of sustainable development is the gross distortion of justice. Bureaucrats who draw lines on maps create instant wealth for some people, while prohibiting others from realizing any gain on their investments. In communities across the country, people who live outside the downtown area have lived with the expectation that one day, they could fund their retirement by selling their land to new home owners as the nearby city expanded. A line drawn on a map steals this expectation from people who live outside the urban growth boundary. Proponents of sustainable development are forced to argue that the greater good for the community is more important than negative impacts on any individual. There is no equal justice, when government arbitrarily takes value from one person and assigns it to another.

Nowhere is this injustice more visible than when eminent domain is used to implement sustainable development plans. The Kelo vs. The City of New London case brought the issue to public awareness, but in cities throughout the nation, millions of people are being displaced, with no hope of finding affordable housing, in the new, “sustainable” community. In Florida, this situation is particularly acute. Retirees have flocked to Florida and settled in mobile home parks to enjoy their remaining days, living on fixed incomes, too old or infirm to think about a new income producing career. Local governments across the state are condemning these parks, and evicting the residents, in order to use the land for development that fits the comprehensive plan, and which produces a higher tax yield. These people are the victims of the “greater good,” as envisioned by the proponents of sustainable development.

Less visible, but no less important, is the erosion of individual freedom. Until the emergence of sustainable development, a person’s home was considered to be his castle. William Pitt expressed this idea quite powerfully in Parliament in 1763, when he said:

”The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the force of the crown. It may be frail – its roof may shake – the wind may blow through it – the storm may enter, the rain may enter – but the King of England cannot enter – all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement.”(24)

No more. Sustainable development allows king-government to intrude into a person’s home before it becomes his home, and dictate the manner and style to which the home must conform. Sustainable development forces the owner of an existing home to transform his home into a vision that is acceptable to king-government. Sustainable development is extinguishing individual freedom for the “greater good,” as determined by king-government.

Conclusion

The question that must be asked is: will sustainable development really result in economic prosperity, environmental protection, and social equity for the current generation, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs?(25)

Even in the early days of this century-long transition to sustainability, there is growing evidence that the fundamental flaws in the concept will likely produce the opposite of the desired goals. Forests that have been taken out of productive use in order to conform to the vision of sustainable development have been burned to cinders, annihilating wildlife, including species deemed to be “endangered,” resulting in the opposite of “environmental protection.” Government- imposed restrictions on resource use in land that is now designated “wilderness,” or “buffer zones” have resulted in shortages, accompanied by rapid price increases that result in the opposite of “economic prosperity.” In sustainable communities, it is the poorest of the poor who are cast out of their homes to make way for the planners’ visions; these victims would not define the experience as “social equity.”

Detailed academic studies show that housing costs rise inevitably as sustainable development is implemented. Traffic congestion is often worsened after sustainable development measures are installed.(26) And always, private property rights and individual freedom are diminished or extinguished.

Sustainable development is a concept constructed on the principle that government has the right and the responsibility to regulate the affairs of people to achieve government’s vision of the greatest good for all.

The United States is founded on the principle that government has no rights or responsibility not specifically granted to it by the people who are governed. These two concepts cannot long coexist. One principle, or the other, will eventually dominate. For the last 15 years, sustainable development has been on the ascendency, permeating state and local governments across the land. Only in the last few years have ordinary people begun to realize that sustainable development is a global initiative, imposed by the highest levels of government. People are just beginning to get a glimpse of the magnitude of the transformation of America that is underway.

The question that remains unanswered is: will Americans accept this new sustainable future that has been planned for them and imposed upon them? Or, as Americans have done in the past, will they rise up in defense of their freedom, and demand that their elected officials force the bureaucrats and professionals to return to the role of serving the people who pay their salaries, by administering policies enacted only by elected officials, rather than conspiring to set the policies by which all the people must live.

Endnotes

1. Sierra Club eco-regions: www.sierraclub.org/eco-regions/

2. Wilderness.net (www.wilderness.net/index.cfm?fuse=NWPS&sec=fastFacts), a project of the Wilderness Institute, the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center, and the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. (October 27, 2005)

3. Campaign for America’s Wilderness (www.leaveitwild.org/psapp/view_art.asp?PEB_ART_ID=397) (As of May 1, 2005)

4. See Eco-logic Powerhouse, November, 2005, and www.eco.freedom.org/el/20020302/biosphere.shtml

5. Agenda Item 1(7), Report of the First Meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice, Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Second Meeting, 6-17 November, Jakarta, Indonesia, (UNEP/CBD/COP2/5, September 21, 1995).

See also: www.freedom.org/prc/legis/hr901test.htm.

6. “How the Convention on Biological Diversity was Defeated,” Sovereignty International, Inc, 1998 – www.sovereignty.freedom.org/p/land/biotreatystop.htm .

7. “Measures for conservation of biodiversity and Sustainable Use of its Components,” Global Biodiversity Assessment, Cambridge University Press for the United Nations Environment Program, Section 13.4.2.2.3, p. 993.

8. Reed F. Noss, “The Wildlands Project,” Wild Earth, Special Issue, 1992, pp.13- 15. (Wild Earth is published by the Cenozoic Society, P.O. Box 492, Canton, NY 13617).

9. Report to the Interagency Grizzly Bear Working Group on Wildlife Linkage Habitat, Prepared by Bill Ruediger, Endangered Species Program Leader, USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Missoula, MT, February 1, 2001. See also: www.eco.freedom.org/el/20020202/linkage.shtml.

10. See: www://clinton4.nara.gov/PCSD/

11. See: www://clinton4.nara.gov/PCSD/Publications/suscomm/ind_suscom.html

12. “Community Sustainability; Agendas for Choice-making and Action,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, September 22, 1995. See also: www.eco.freedom.org/reports/sdagenda.html

14. See www.eco.freedom.org/col/?i=1997/9 And http://www.sovereignty.net/p/sd/suscom.htm For a discussion of the consensus process, and sustainable communities.

15. International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives web site, October 28, 2005 (www.iclei.org/index.php?id=798)

16. Summary of the Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook, 2002 Edition, (www.planning.org/growingsmart/summary.htm)

17. State of Wisconsin, Department of Administration web site: www.doa.state.wi.us/pagesubtext_detail.asp?linksubcatid=366

18. FoxNews.com, July 10, 2004 www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,124358,00.html

19. See www.worldcarfree.net/links/traf.php.

20. See www.worldcarfree.net/links/traf.php for descriptions of these housing alternatives.

21. “Forfeiting the American Dream: The HUD-Funded Smart Growth Guidebook’s Attack on Homeownership,” The Heritage Foundation (www.heritage.org/Research/SmartGrowth/BG1565.cfm), July 2, 2002.

22. “Eminent domain; eminent disaster,” Eco-logic Powerhouse, August, 2005 (www.eco.freedom.org/articles/maguire-805.shtml) , for a discussion on this issue.

23. President’s Council on Sustainable Development, We Believe Statement #8 www.sovereignty.freedom.org/p/sd/PCSD-webelieve.htm

24. William Pitt, the elder, Earl of Chatham, speech in the House of Lords.–Henry Peter Brougham, Historical Sketches of Statesmen Who Flourished in the Time of George III, vol. 1, p. 52 (1839). (http://www.bartleby.com/73/861.html)

25. Sustainable Development as defined by the U.N.’s Bruntland Commission report, Our Common Future, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 43

26. This website, www.demographia.com/dbr-ix.htm provides an abundance of reports and studies that challenge effectiveness of sustainable development.